She is correct, as is often the case on the show. If Fox Mulder is a hero, he's a tragic one; and much like Captain Ahab he would rather stab at the mysteries of life from Hell's heart in his dying breath than simply live with it. Just look at the body count in any given episode, and how many of those deaths are collateral damage to his efforts. Look at his lack of a social life, which eventually becomes mirrored by the same in Scully's life. Mulder was an obsessive paranoiac, but the difference between him and the average tinfoil hat researcher is that the government paid him to be that way. This is not to say Mulder didn't have his admirable qualities; of course he did, and as much as Homer Simpson came to symbolize the everyman Mulder came to be an avatar for truth seekers and DIY researchers of all walks of life. The irony seems to be that in choosing him as a role model, real-life pursuers of the Truth-that-is-out-there miss the subtle cautionary tale inherent in the story. The history of Ufology in particular includes many examples of those who have discarded their lives - whether intentionally or otherwise - under the pretense of revealing the Truth to the public. Many today in the Disclosure movement would do well to heed the warnings offered by Mulder's example, but, as is often the case, he is instead idolized as an example to follow. The path that Mulder's flashlight illuminates is one that leads to madness; one should, instead, seek the yin and yang of both lead characters together, rather than one or the other.

Speaking personally, one particular episode that embiggened my consciousness in the same subliminal way Simpsons references occasionally manifest in my speech is "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose" (Season 3, episode 4). The episode is written by Darin Morgan, who wrote all of my favorite episodes of the show. These include "Jose Chung's From Outer Space", which is perhaps the single best fictional presentation of high strangeness and the difficulty inherent in making a cohesive story appear from it; "Humbug", which centers on circus and carnival characters; and, when the series returned for a brief run, the two best episodes "Mulder and Scully Meet the Weremonster" and "The Lost Art of Forehead Sweat". In addition, he appeared on the show in "Small Potatoes", and played the Flukeworm Man in the episode "The Host".

If all of that isn't enough, he also helped to write the aforementioned Ahab dialog in "Quagmire", although he didn't write the main episode. Morgan has a way of tapping directly into the quintessence of the great mysteries, by way of well-crafted stories in which Mulder and Scully are forced to contend with the purely absurd. Often funny and always charming, his contributions in the form of "Monster of the Week" episodes utilized that very humor and charisma to convey the nature of anomalies in a way that few dramatic interpretations can ever hope to achieve.

Such is undoubtedly the case with "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose". Peter Boyle guest stars as the titular character, an insurance salesman who is worn down by life and feels he is cursed with psychic abilities. Mulder is able to sense this about him, and Bruckman reluctantly agrees to aid he and Scully in the investigation into murders of fortune tellers in his native Saint Paul, Minnesota. His main ability seems to be knowing precisely the manner and time of a person's death, well before it happens- so of course, he sells life insurance. He seemingly predicts Mulder's death with an off-hand comment about auto-erotic asphyxiation, and famously tells Scully that she doesn't die. The part of the episode that impacted me, and my worldview, went largely forgotten for years and was only discovered when I revisited the series long after originally seeing it.

Bruckman explains how he developed his abilities, more or less by accident, after hearing about the death of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. He explains that in 1959 he had a ticket to see the three rock and roll legends play what would have been their next stop, had their plane the American Pie not crashed. He was particularly excited to see the Big Bopper, known for his song "Chantilly Lace"- and found out later that the only reason the Big Bopper got a seat on the plane to begin with was that he had flipped a coin with someone else for it. (In real life, this did happen, only it was Buddy Holly who had flipped the coin to win a seat on the plane. We can forgive Morgan for this inaccuracy though!) Bruckman became obsessed with the coin flip, and realized that all of life is composed of little moments that lead to something so small as a coin flip- which could mean the difference between life and death for even so great a personage as the Big Bopper. His obsession with causality, and imagining the myriad factors and variables which manifest in everything that can be said to happen, eventually led him to accurately determine when someone would die- and how. "I know it sounds crazy, but I swear it's true!" he says, "I was a bigger fan of the Big Bopper than I was of Buddy Holly."

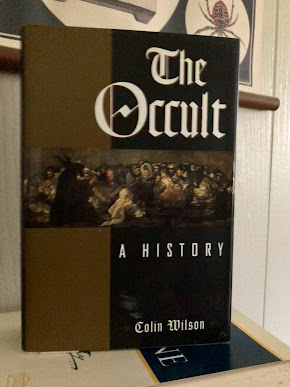

I never necessarily considered myself to be psychic, but I have long believed that all human beings (and all life forms, for that matter) have some degree of sensory perception that is as yet not understood by modern science. Some are naturally more adept at accessing the information, while for others it takes dedicated practice- but each of us has some germ of omniscience within us. Colin Wilson calls this idea "Faculty X", in his excellent book The Occult: A History, which I always recommend to people who are only beginning to explore occult ideas. He supposes that ancient man, unfettered by the distractions and conveniences of modern life, would have had innate extrasensory perceptions that enabled him to survive in a chaotic and dangerous world. Some remnant of that still exists, and there are many schools of thought about how one harnesses this awareness. I felt pretty clever for years, thinking I had just stumbled on the idea that simply by considering causality I might have some inkling of future events. It was never easy for me to explain, which was fine because I rarely had anyone sympathetic to whom I could explain it- but the nature of Time, whibbly and wobbly as it is, is merely illusory. We experience it in a linear way because otherwise, our minds would break. By perceiving all that is happening now- by really paying attention and noting what's going on in your immediate environment, in meditative silence, one just might be able to perceive what has happened and what will occur. Further, by considering why everything you perceive at any given moment is occurring, you glimpse a bit of the machinery, which trains the mind to anticipate how that same machinery will operate moving forward.

As I type this now, in my living room with my small dog curled up next to me on the couch, I can see outside that the storm is winding down to a light drizzle. Birds are chirping in the distance. My wife has gone out shopping, which inspired me to start typing this. All of these present affairs are intimately interrelated. Had it not stormed today, my wife would have insisted on going to the flea market- or, perhaps, would have preferred to go shopping further away- but since she doesn't like driving in the rain, she stayed closer to home. Had we gone to the flea market, I wouldn't be writing this right now- and if I wrote it later, it would undoubtedly be a very different meditation indeed. These are small examples of immediate awareness of the NOW, which is a window into the WHAT COULD HAVE BEEN- and, quite possibly, also a window into WHAT WILL BE.

The preceding paragraph is an homage to Wilson. When I first read The Occult, I found myself getting irritated as his asides about his personal life. In explaining Faculty X, he would often say "As I sit at my typewriter in my home in Cornwall..." and for some reason I just found it tiresome. One day while reading it I became sleepy and went for a nap. I fast fell into a dream, in which I opened a door and suddenly all that I could recognize as my own dreaming was gone- I found myself in a small room, built of stone with large windows letting soft light in. It was large enough for a few benches, on which sat Colin Wilson. He smiled, and shrugged, and as though answering a question I hadn't asked said "It's about honesty, isn't it? Are you being honest, that's the main question. Everything else depends on that." I woke up mystified. I wasn't sure at the time that I even knew what Wilson looked like- my copies of his books didn't have author photos. I eventually remembered an obituary of his in an issue of Fortean Times, and dug it up- and there he was, older than the Wilson of my dream but recognizable. A few google searches later found photos that looked much more like the man in the dream.

Ever since then, I have always endeavored to be honest with myself first and foremost, and honest in my approach to writing in particular. This sounds easy, as most of us like to think we're naturally honest people- but when you really examine it, you realize that there are little lies you tell yourself all of the time. Confronting these demons, as it were, and banishing them, also helps to promote Faculty X. This digression and admission of potentially psychic activity is oddly difficult for me to express. It sounds crazy. In the interest of being honest, however, it felt natural to include it- and for the record, I'm a bigger fan of Buddy Holly than I am of the Big Bopper.

It was wild then, for me, years after digesting a great episode of such an iconic series of The X-Files, to realize that so much of my way of looking at the world was inspired by the fictional character of Clyde Bruckman. (The real life Bruckman, as it happens, is a tragic character in the history of old Hollywood. The name stuck in my memory because I recognized it from the credits of old Laurel and Hardy or Three Stooges films... This is a running theme in The X-Files, which I will have to write about another day. The writers seemed to love referencing old comedies.) One wonders, had I not seen that episode when it first aired how different my life would be. If one does wonder that, than one has caught on to the idea of causality that I'm describing, that I learned through Darin Morgan's writing.

These themes weave themselves through the so-called "Monster of the Week" episodes in a way that is only apparent to the real nerds who pay attention to such things. The episode "Monday" (Season 6, episode 14) is a Groundhog Day-esque time loop tale, wherein events that come to pass largely due to lasting effects from the temporal jiggery-pokery that occur in "Dreamland" (2 part story, episodes 4 and 5 of the 6th season) cause Mulder to continually end up at a bank while it is being robbed, and repeatedly die in an explosion. Since Bruckman's insights might have saved Mulder's life in that episode, it seems by virtue of the fact that future events were disrupted a ripple effect had a lasting influence later in the series. Also, the dog called Queequeg was introduced in "Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose"- and done away with in "Quagmire". The dog's name is what inspired the Ahab comparison in that episode.

In 30 years the legacy of Mulder and Scully, and other characters like the Lone Gunmen and the sinister Cigarette Smoking Man have loomed large in our public consciousness when it comes to anomalies, and in particular to UFOs. To this day, when news stations cover a UFO story, they can't help but insert the theme song, much to the chagrin of dedicated and serious researchers. I hope that future generations continue to discover the show, and perhaps with hindsight glean some of the subtler lessons the show had to teach. A major Truth that is out there for any of us to catch is that being serious all of the time does not necessarily bring one closer to their goal. Perhaps the quote to end with would be the line Leonard Nimoy gives, at the start of the X-Files / Simpsons crossover episode, "The Springfield Files":

"...and by 'true', we mean 'false'. It's all lies. But the lies are told in an entertaining fashion, and in the end, isn't that the real truth?

The answer is no."

No comments:

Post a Comment